|

Letter

to the editor

The ASCAP Bulletin Vol.2, No.2 April 2001

What

is a story?

Every

story has a beginning, a sort of action and an end. Let us start

with

short stories: A becomes B or A goes from B to C. In biology, more

precisely

in ethology, we call this type of short stories an episode or an

actugenetic

event.

A single eyeblink, the reaching for a food item or the journey some

birds do every year across thousands of miles are examples. Because

of the closure of the NS only seldom you can say when an action

starts or ends. Fuzzy temporal and anatomical borders are common

but identity of the performer is usually preserved; the eye, the

hand or the bird.

Good stories often offer more than one episode, more complexity

is

easily obtained by meshing one story within another story. The best

story-box is (the memory of) a human story-teller who everyone of

us is.

Let's look into our lifetime as a unique story with at least two

parts so far, from birth to reading these lines and from here to

where you go or what ever you do. But now please take serious the

proposition that every movement of our body is part of our personal

story-line which is the very line our body draws through space and

time.

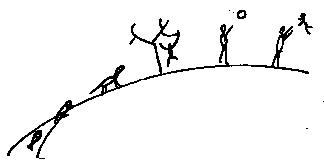

After birth we are carried around above ground level, later we crawl

on it slowly on all four limbs, then the very first steps - the

line of that event is usually remembered in all details: starting

point Mama - three, four or six delicately balanced steps - endpoint

aunt Mary or - less often - Papa.

We can imagine the daily routes of walking, driving, shopping, visiting

any place inside the flat or anywhere in our home-town - and every

evening we arrive at the same point of return or rest: our bed (except

bachelors).

We move to another town, we fly into holiday or climb mountains

- in principle all movements we perform during our life time can

be seen as one line - drawn continuously by our center of gravity

(which can virtually represent the whole body in one point placed

somewhere near the stomach).

For our cognitive life we must take the labyrinth of the inner ear

as the very instrument to draw the life-line: It perceives every

acceleration in all directions, rotations in particular, and it

can judge distances of being carried (or even

being driven) quite precisely. The labyrinth is the first sense

to be alert in our lives (12th week of gestation) and probably is

also our last one working.

In short: The ceaseless chain of single behavioral episodes stored

in biographical memory makes a life-line. Actugenetic situations

are the micro-elements of ontogeny - and locomotion is the performing

part.

The story of all stories, as you know, is evolution and we are concerned

here with the phylogeny of vertebrates including ourselves.

Is it a story of success? - yes.

Is it also a story of "ascending" development?

A story of reaching higher levels: yes. Fish started below sea-level,

amphibians mounted the shores, mammals lifted their bodies from

ground and primates climbed the trees. Then there was a "down"

with hominids returning to the ground-level, but by lifting their

forelegs together with the front half of the body they started the

most impressive (and still unexplained) story of all, hominisation,

becoming human. Cooperation enabled them to reach the highest level

so far, the orbit of the moon:

Again we can say that evolution is the succession of innumerable

ontogenies, from the first paleozoic fish to everyone of us.

In this way evolution is a locomotor story.

|