|

Proceedings

of the 26th Goettingen Neurobiology Conf. 1998 Vol 1

Ed: Norbert Elsner & Ruediger Wehner

Georg Thieme, Stuttgart, N.Y.

Locomotion

and Cognition: From fish to hominids

Movement is the first product of the nervous System

- is it also its last riddle?

Vertebrate behaviour and cognition seem to have originated in fish.

Every movement of the tail of a fish or of its fins will change

the position of the fish in (relation to) its environment. These

changes are received by the sense organs: locomotion produces locosensation.

Or in the words of Ragnar Granit: "Muscle moves the world".

Not only our first ancestors were mobile, so, too, were their first

life-essential objects: prey, partners, competitors and, perhaps,

predators. The cognition of fish has to take note of three moving

bodies: itself, its shifting environment and the other animal. The

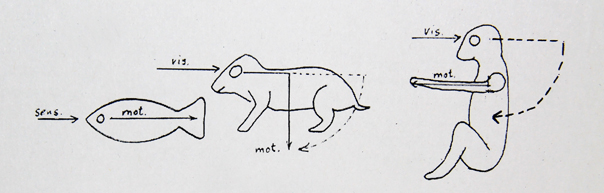

nervous system produces (rhythmic) motor patterns and perceives

environmental changes according to these patterns ( figure A).

The next step towards mankind were the tetrapodes. As with

fish, their eyes continue to scan the horizon, but the direction

of their (loco)motor activity has bent by 90° ( figure B). Reafferent

information's are coming from the limbs, additionally. The importance

of this internal feedback is that body parts can now move without

influencing the environment. Locomotor patterns are thus "fed

back" via exafferent patterns (environment shift) and via reafferent

sensory patterns.

Primates have four hands to make contact with the arboricole

environment. They prefer to sit, moving their arms freely to reach

and grasp. Their locomotor apparatus has begun to split:

While seated, the hind limbs and the pelvis are engaged in "nonlocomotion",

but the arms and hands bend again by 90° and appear in the frontal

visual field (actually this bend developed between head and neck,

figure C).

For the first time in the evolutionary process, animals can watch

directly and for extended periods of time what parts of their body

are doing. Arm and hand motor patterns are also sensed twice: By

reafference and by the newly possible visual control. When the nervous

system takes notice of the synchronicity in this closed motor-visual

loop, the eye-hand complex can develop. Does this indicate that

hands, objects which hitherto were known only as parts of the environment,

have been "recognised" as parts of the subject? Can we

assume that "self- recognition" has taken place?

In hominids the eye-hand-complex permanently works in an

autonomous manner. Even during locomotion, arm and hand movements

are "movements of their own", independent of the actions

of the hind limbs. Tools are now endowed with self-moved quality,

throwing extends the distance reachable, the individual can recognise

his own shadow and perhaps also his own face moving in a smooth

surface of water.

Fig. A,B,C

|